‘Things Have Come Undone’: At Home with the Millions of People Who Owe Billions of Dollars During COVID

"I cried all day today," says 25-year-old Victoria Williams, who lost her housekeeping job last March at an all-suite hotel near the French Quarter in New Orleans as COVID-19 spread.

"I wake up every day and think, What next?" Williams says. "I don't know who to call."

This is what it sounds like to talk to the renters left in limbo amid a pandemic that has now killed more than half a million people in the U.S. The economic damage from the public health crisis — the businesses shuttered and the jobs cut as people retreated to their homes and governments imposed restrictions to slow the spread, with nearly half a trillion dollars lost in the economy — is another enormous toll.

It all happened at exactly the wrong time: The number of renters in the country has risen sharply since the housing market crash at the center of the Great Recession, and many of those people were already stretched beyond their means because of rising rental rates.

Once the work stopped and the paychecks stopped, millions went into free fall, reaching for their savings, their credit, outside aid: some kind of safety net.

Williams and her restaurant-dishwasher boyfriend had been living with her mother in New Orleans when she lost her job. But her mom couldn't pay the rent and moved in with a relative, so Williams and her boyfriend found an apartment, despite the fact that they were both unemployed. "They said they would work with us," she tells PEOPLE. The couple used their savings and a combined $287 in weekly unemployment benefits to get them through.

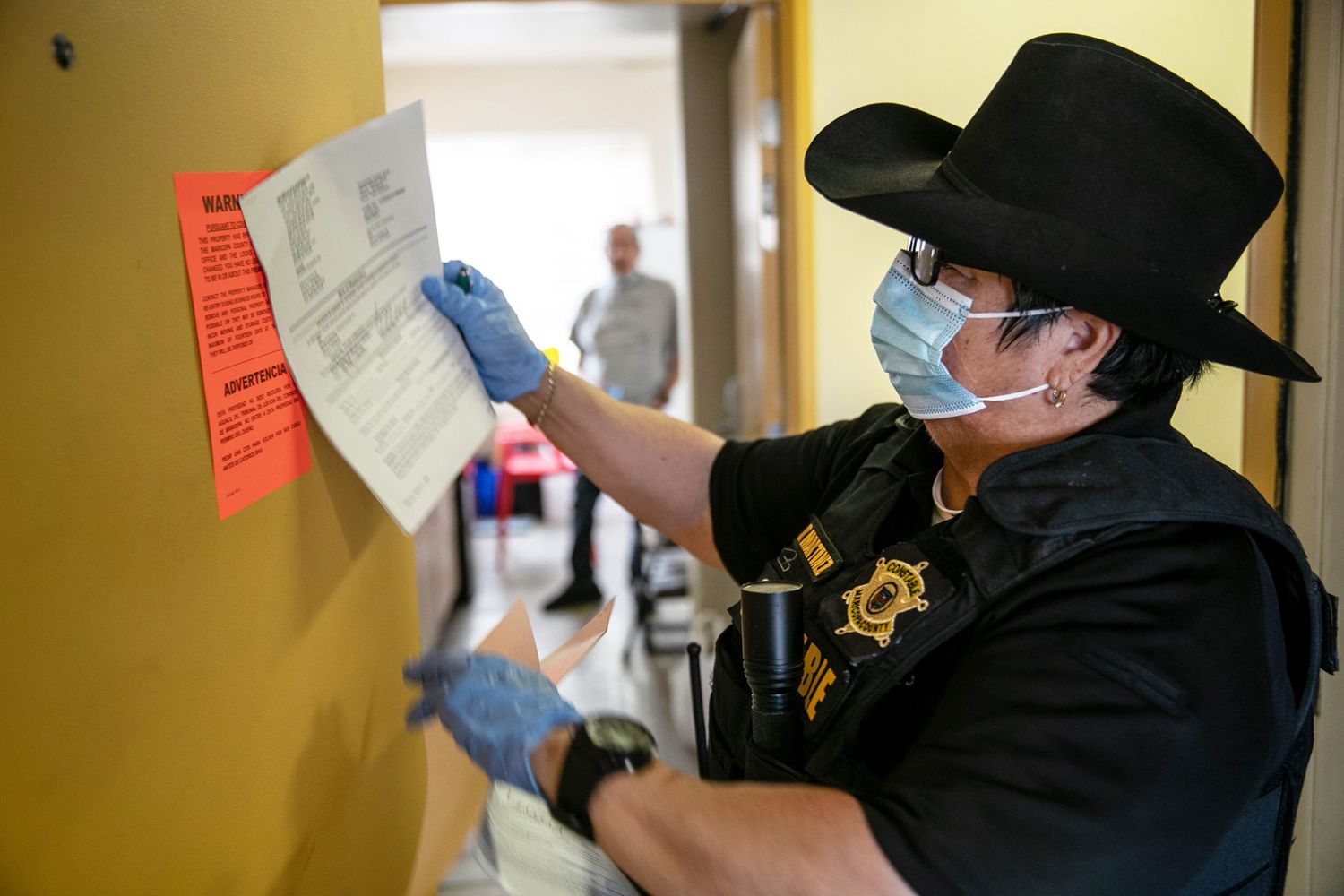

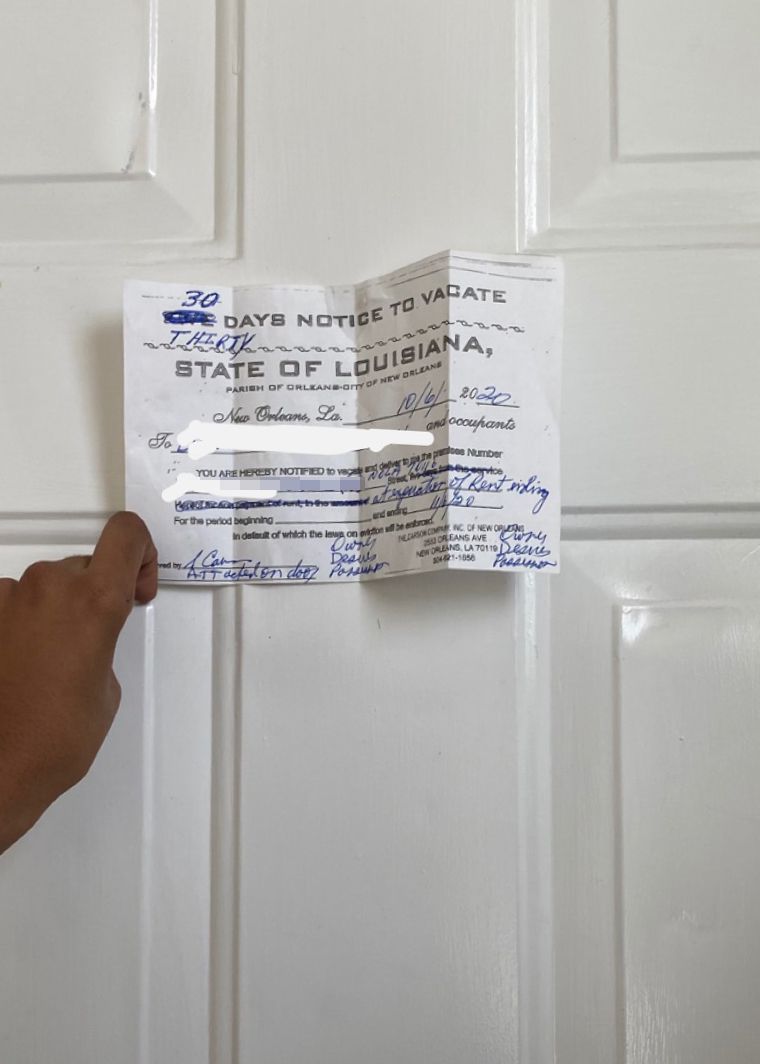

They kept up with the rent for few months, but pretty soon their savings ran out. In October, they offered to pay partial rent. The landlord refused and posted an eviction notice on their door, Williams says. She panicked, and after many phone calls for help she found a legal-aid lawyer and got the eviction dismissed.

It was a temporary respite. Jobs haven't materialized in the city sunk by the lack of tourism, with this year's Mardi Gras essentially canceled. The couple has collected unemployment and stimulus money — starting in January, they also received $300 each when the government boosted weekly benefits. But Williams and her boyfriend have been getting $887 a week, it won't cover the more than $2,400 they owe in back rent. They'd like to offer partial payment. "We want to pay as much as we can, if we can get an inch out of them," Williams says. "They haven't been responding." She's applying for work, but she broke her ankle falling down the stairs, so now she needs a job that doesn't require standing.

She applied for renter's assistance twice, but it hasn't come yet. The couple is dependent on the uncertain fate of the government's intervention: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention placed a nationwide moratorium on rental evictions last September, with the intention of stopping the spread of COVID-19.

Williams' pending eviction was dismissed only because of the CDC-imposed ban.

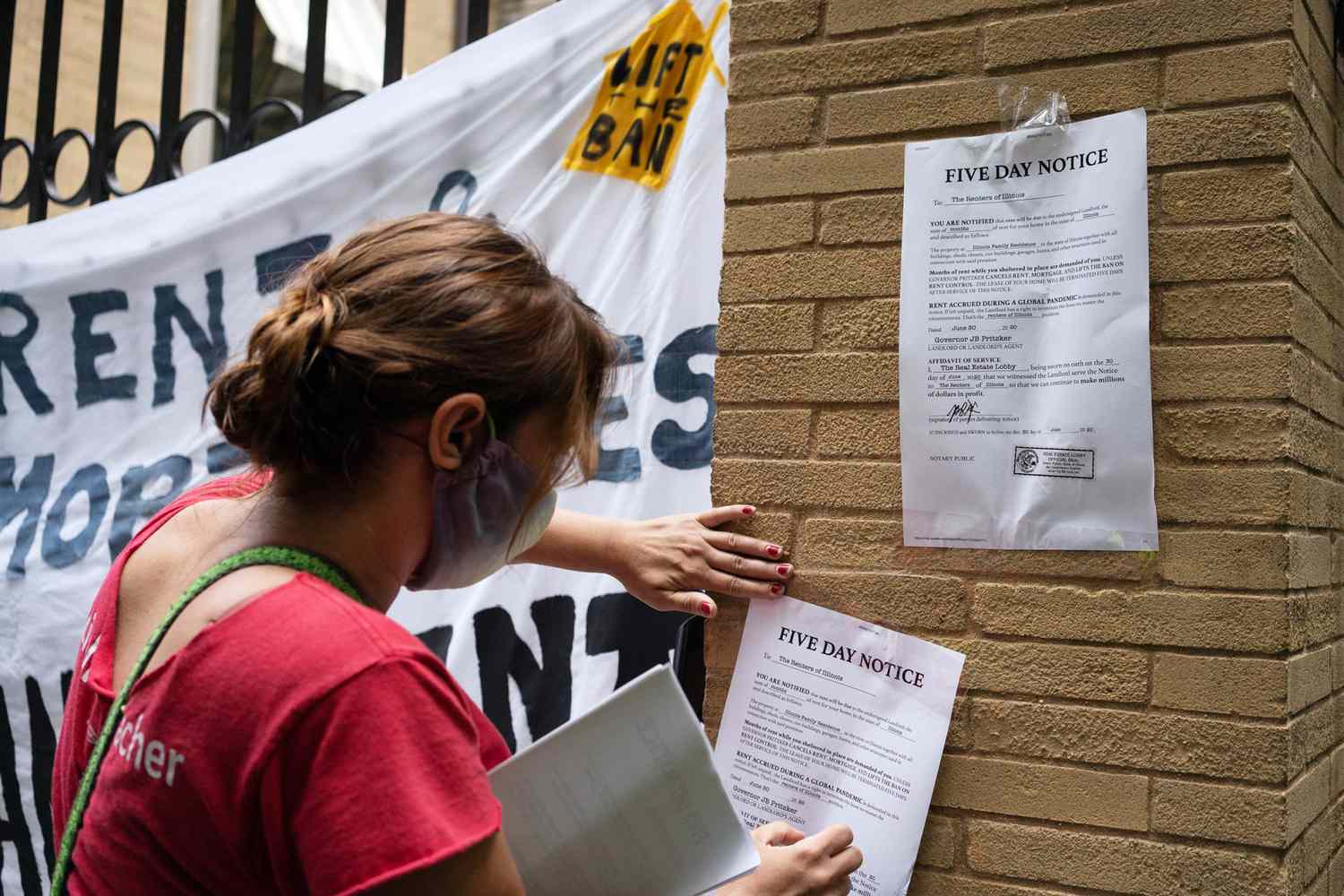

After two extensions, that moratorium now ends on March 31. The deadline looms in the minds of many renters, though some states and jurisdictions have set their own restrictions that extend further. A group of Texas landlords is fighting to have the federal moratorium tossed, and a judge there agreed — ruling in February that it was unconstitutional, though he did not issue an injunction. The Department of Justice is appealing. (On the other end of the country, New York landlords gathered to protest a similar state ban on evictions.)

If Williams and her boyfriend are kicked out when the moratorium is lifted, she says they will probably put their furniture and belongings in storage and live in a hotel.

"Patience," she says tearfully, "is all I can have right now."

As of now, some 6 million renters like Williams are behind on their payments and at risk of eviction, analysts say. Many of these people became unemployed in the wake of COVID-19's spread in the U.S. Now, they no longer qualify to rent their current home, aren't likely to be able to move to a new rental and are at risk of becoming homeless.

As the pandemic has forced incomes to decline or even evaporate, bills have become unreachable. But the economic disruptions have not hit everyone the same way: A public health emergency from an airborne virus has particularly upended places where people gather. The hospitality and leisure industries have lost millions of jobs in the last year. Restaurant workers, employees in personal services and social services and education as well as government employees have also all suffered paycheck cuts or job loss. Employment in some sectors continues to plummet.

Nearly one-third of renters fell behind on rent right away. Analysts have been sounding the alarm that without sustained financial support — through a large-scale jobs program, for example, or increased government assistance — hundreds of thousands of more adults could fall into homelessness in the next few years.

The CDC's eviction moratorium is reasoned from this grim reality: If people were kicked out of their homes for non-payment they would resort to living with relatives or friends in an overcrowded situation or even become homeless, and that would likely increase infections.

Courts across the country are flooded with eviction cases waiting for the day the ban lifts. The average renter who is delinquent owes thousands in back-rent, and many of them still don't have a decent paycheck. Direct-relief payments (like the stimulus checks) as well as boosted unemployment benefits and $25 billion in rental assistance for qualified tenants have already come to the rescue from federal coffers. More help is coming, the White House says.

The total number of delinquent renters is dropping, down to 6 million from some 9.4 million people in January, and advocates have lauded the cash infusion to those in need. But they say problems remain. "Current levels of support for emergency rental assistance are critically important during the pandemic, but we also need sustained federal support for affordable housing," says Vincent Reina, an assistant professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of Pennsylvania.

What's more, landlords don't have to accept rental assistance from the government that comes with stipulations, such as accepting partial payment, agreeing not to evict for a certain amount of months or registering their property and opening themselves up to broader regulation.

"I don't have many options," says Illien Thamer, a 50-year-old California resident who was barely making ends meet before the pandemic. When the schools closed, Thamer lost her job as a special education teacher's aide and her 10-year-old son returned home. They have been living in a $1,200 per month one-bedroom apartment in Redondo Beach. Thamer fell behind on rent but paid what she could. She now owes more than $13,000, but she says the landlord refused the government rental assistance she secured.

There is good news: School just opened, and her son is back in class a couple of days a week. Thamer also got her job back as a half-day teacher's aide for special education. But she's still not making enough to cover her rent. She has applied for assistance that will come directly to her and doesn't require the landlord to sign off. And even though it won't cover the full amount due, it will go a long way, she says.

California is a tenant-friendly state, which also has its benefits: The state's eviction moratorium goes through June 30, longer than the CDC ban, and renters with a coronavirus hardship can defer missed rent without incurring late fees.

But that cannot compel a landlord's cooperation for other problems.

Thamer's landlord had the gas shut off after a leak last June and never had it fixed, she says. So she and her son go elsewhere to cook and bathe because they can't use the stovetop or get hot water. The landlord clearly wants them out. A process server with an eviction notice came inside her apartment, Thamer says, and "I was freaked out." The notice said she had 30 days to vacate. With the help of an attorney, the case was dismissed last month. The landlord still hasn't fixed the gas, though. She says the California Department of Consumer Affairs has gotten involved.

Thamer fears she can't move while she's in such a dire financial position. Besides that, she lives in a hotspot: "I'm afraid to move because of the pandemic going on — people are getting COVID."

(The landlords in the rental situations described here have not commented for this article. The identities of certain renters, whom PEOPLE did not reach, have also been withheld.)

Heidi Breaux knows fear, too. She owes $5,000 in back rent and counting and she says her Baton Rouge, Louisiana, landlord harassed her with texts, calls, knocks on her door and three eviction notices. "I worry every day," she says. "I've been to eviction court three times." The conflict died down after her last court date, though she knows she's not in the clear. Her other creditors have worked out payment plans with her, but she says she couldn't get her landlord to budge. "Everybody else understands — it's a pandemic. We're all going through the same thing," Breaux says. "I don't know why [the landlord] is being so crazy. I'm paying as I get paid and the court said they have to accept it."

Without the protection of the CDC's eviction ban, "I'll be homeless," Breaux says. "Me and my two daughters will be homeless."

She was working two jobs, including as a cashier at a grocery store. But when the pandemic hit, she quit because her daughter has asthma and she wanted to reduce her exposure. After Breaux's relationship with her boyfriend ended, she moved with her daughters into a two-bedroom townhome in the same school district. But the virus was never far away: When her babysitter contracted COVID at the end of June, Breaux had to quit her data-entry job at the Louisiana Department of Revenue to take care of her daughters, then 10 and 12.

She collected unemployment while she looked for work and didn't find a new job until November, when she was hired as a full-time custodian at a church day care. Of course the bills don't stop: By then she'd gotten behind on her rent, electricity and car payments. Even though Breaux has a steady income now, she can't cover what is past due. She's using food assistance to feed her family, and she was approved for rental aid, though she says the landlord refused. Her children are physically back to school, but they're often home again for quarantines. Her older daughter suffered two asthma attacks in the past year, but she still has to go to school when it's open because Breaux can't afford to miss work.

"I've never experienced this before," she says.

The average delinquent renter in America right now owes $5,282 and is more than three months behind. Their stories are so many; the pain is deep. This article could have been 10 times longer.

What Got Us Here

"You saw people already extending themselves — particularly the lowest income households — as far as they could to afford their housing," says Reina, the University of Pennsylvania professor. Housing prices and rents had grown faster than incomes. Even before the pandemic, a majority of renters in the U.S. — 20 million-plus households — were cost burdened, spending more than a third of their income on housing, according to the federal government.

Advocates have been calling for more government funding of affordable housing for years. By the end of 2020, the median rental price for a vacant unit had reached an all-time high of $1,190. In 23 states and the District of Columbia, a full-time worker would have had to earn $20 per hour or more — well above national and state minimum wages — to afford a two-bedroom rental home with only 30 percent or less of income going to housing, as is recommended.

People of color were disproportionately affected by affordability: More than half of Black and Hispanic renters were already shuttling more than 30 percent of their income to housing even before the pandemic, which was a significantly higher proportion than white renters, according to Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies.

And then the pandemic made everything worse, Reina says.

Many of the tenants who are still able to pay their rent are doing so through desperate means, he says: "They're extending their credit in every way, shape and form, through family, through payday loans, through credit cards, through whatever conventional and unconventional forms of financing they can find to pay their rent. Households are showing extreme signs of economic distress both through rent owed, but also through other forms of debt that they've extended themselves."

Reina notes that because some landlords are refusing government rental assistance because of the attached stipulations, some renters who qualify for assistance are unable to take advantage of it.

By late September, the month the CDC moratorium was issued, people of color were much more likely to get behind on rent payments: Almost a quarter of Black renters and one in five Hispanic and Asian renters were past due on their rent payments. That was twice the 10 percent share of white renters, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies. Black women also faced a higher rate of evictions than Black men, TIME reported.

That is only one troubling dynamic. Black, Hispanic and native people are also disproportionately likely to be hospitalized or die from the coronavirus.

The eviction ban by the government came as a surprise. "A significant housing intervention is fairly unprecedented," Reina says. But he said it was needed: "There was a severe lack of support for the group being most affected, by both the disease and the economic repercussions of the disease. In many ways, this was an absolutely necessary step to help stabilize the livelihoods and literally the lives of our residents."

Immigrants who are in the country illegally have been excluded from the federal government's aid, though their needs are very real: "There's been nothing to help," one woman told ABC News this month.

The support landlords say they need and the complications they say they are contending with, trying to rent property in a pandemic, is the other part of this story.

Many property owners refuse government rental assistance because of the concessions attached to it, which vary around the country. Reina's group, The Housing Initiative at Penn, surveyed some owners in Philadelphia and found that they objected to the requirement to forgive back-rent, for example, and were upset that the money offered by the government would not cover the full bill. A broader survey found that most assistance programs also required the landlord to commit that they would not evict the tenant for one to seven months, or even longer. Some aid required a current rental license that many smaller landlords don't have, inclusion in the local rent registry and a promise not to increase the rent for a certain period.

When a landlord refuses to accept government rental assistance, the tenant is still on the hook.

While some municipalities have eviction-diversion programs that mandate mediation between the owner and the tenant to work out payments, it is still not the time to end the eviction moratorium, Reina says. That would lead to a crisis of widespread housing instability."

Housing is so fundamental to well-being, for every person," says Julián Castro, a former U.S. housing secretary and advisory committee co-chair of the Housing Playbook Project, a blueprint for Joe Biden's administration.

"Time and again, it's been demonstrated that having a stable, decent place to live means that someone is more likely to get a better education, have better job opportunities, have better health and so forth," Castro says, "and during this crisis, millions of Americans are on the brink of eviction. It strikes at the heart of dinner table anxieties."

The federal government has helped with stimulus money, extensions on unemployment and $25 billion in rental assistance in the last year. As part of the latest COVID relief package, Congress approved another approximately $27 billion in rental assistance along with $5 billion for emergency housing vouchers for homeless and those at risk of homelessness.

The money matters: In January, the total back-rent owed was $52.6 billion, experts say. Now it's approximately $31.9 billion.

But that is still an enormous number.

"As millions are still unemployed and falling behind on rent, I'm hopeful that Congress will keep working to provide additional relief to meet the need of those facing eviction, homelessness and housing insecurity," Castro says.

"We had a rental affordability crisis before this crisis," he says. "It's deepened because of the COVID experience, and it's going to get even worse in the future when the rents start to spike again like they were before."

If there is at all a silver lining, it is that it has brought the housing issue front and center. "When the pandemic hit and it mostly hit these poor communities, there was all of a sudden a broad discussion about how the housing was not adequate," Castro says. "There was overcrowding, and all of that was leading to a worse situation with COVID. Because a greater swath of Americans are impacted, now there's more of a coalition to press on Washington to actually do something about these issues. There are more middle-class families today that are worried about their housing situation than there were before this pandemic. There are more voices there to call their congressional representative to make their state senator or their city council member aware that housing needs to be a priority."

Castro is concerned about landlords, too.

The government's pandemic assistance has included some provisions for them, such as small-business aid and the Paycheck Protection Program as well as mortgage forbearance and a ban through June on foreclosures for federally guaranteed mortgages.

Castro notes that many landlords are individual owners rather than the kind of faceless property owners backed by corporate funding: "Many of them own a duplex or a fourplex or a single-family house."

Indeed, the federal government says more than 40 percent of the nation's 44 million rental units are owned by individuals — mom-and-pop landlords who, if they own multiple units, are likely to carry a mortgage. The national average total cost to landlords for a rental unit is $830 a month.

When renters can't pay, the landlord's costs don't go away.

‘We’re Hurting and They’re Hurting’

One agitated landlord, Angela Wiley, says that in three decades in the business she has never experienced anything like this. She owns 327 low-income units in Houston, most of them renting for $500 to $900 per month. The pandemic upended her finances: 15 people left without settling up, three people died — one from COVID — and 46 more are behind on rent. Another 22 are able to make partial payments, sending in $100 here and $150 there when they get money. She's out $62,403 total and she sounds like it.

"Each month I wait for the first of the month to see what money I collect," she says. Because the renters know she can't evict, she thinks some are taking advantage. "They consider it free rent. There is nothing to force them to pay."

Some of her tenants who are behind on rent are now getting unemployment or other assistance, "but they're not necessarily using it toward rent," she says. "A couple of them bought cars." The renters may need a car to commute to work so they can get back on their feet, but Wiley nonetheless has a feeling some are simply taking advantage of the situation. When the moratorium is lifted and she finally can evict people, she's worried they'll leave first without paying back rent and may leave her with little recourse.

She just paid property taxes, and she's disappointed that the city didn't make allowances. "I am up to date on the mortgage — I pay two to three months out front — but I've always believed in having a safety net and I don't have that now. I've depleted my safety net," she says. "Now I'm living paycheck to paycheck or rent to rent. When they give me rent, then I pay things."

The deadly winter weather that froze her city last month left her with burst pipes that caved in the roofs of nine apartments. Another 30 properties sustained leaks. Workers fixing the problems need to be paid, and Wiley is working with her insurance company to see if they can give her an advance on her claim.

Still, she's trying to remain sympathetic to tenants. "We're hurting and they're hurting," she says. Many renters worked in restaurants and capacity has been limited. Many others worked in the city's sports stadiums, and that was shut down, too. City buses stopped running for a while because drivers were out with COVID. Wiley knows the situation is dire for many, and she would take no pleasure in seeing anyone evicted. "You have to be gentle in this situation," she says. "This is all they have. People have nothing and you're going in and telling them, 'I am going to take the last nothing you have and make you move.' "

She now spends more time in the office so that a tech-savvy employee is free to help elderly tenants file for assistance on the company computer — as local libraries were closed — so renters can perform the video self-inspections required for housing vouchers. Wiley previously spent more time looking for new properties to purchase and renovate. "We have to help people to get money so they can pay," she says. "This is not going to work for much longer. We're going into a full year. We've got to come out of this."

Wiley has 67 vacant apartments, half of which need to be remodeled before she can rent them. That's on hold. The others need minor repairs, and that has also been a challenge during the pandemic. The local hardware store closed for a while and it's taking months to get necessities like refrigerators.

This situation is better now. There were hours-long lines after the winter storm, but now supplies are easier to come by, although she still has appliances on back order.

Steve Tennison, who owns 98 apartments in a two-story garden-style complex in north Houston, has been lauded by the local apartment association for going out of his way to help renters. Business was going well before COVID. Last April, tenant after tenant started coming in with "empty pockets," Tennison says. "It was awful. Our residents just started dropping like flies — not, you know, literally, but they just started not being able to pay. And they were coming to us saying, 'Hey, I got laid off.' 'I got my hours cut.' 'Uh, my boss said go away, I don't know when I can call you again.' "

"People weren't paying late because they were just lazy or irresponsible with their money," Tennison says. "They were late because their cash flow just went from whatever to zero, and it wasn't their fault. We had good people who have been living here for years and being on time, good customers, and all of a sudden they're coming in and saying, you know, what do I do?"

"There's a weird misconception about landlords that everybody thinks we want to kick people out," Tennison says. "We don't want to kick people out. We hate kicking people out. Those are our customers. We love them. They pay the bills."

Meanwhile, "I was watching my bank balance go lower and lower," he says. "I'm trying to figure out how to handle a situation that is unprecedented. None of my friends who own apartment complexes knew what to do. The Houston Apartment Association didn't know what to do. My bank didn't know what to do. All we did was deal with the situations that came at us day by day, and all my owner buddies kept in touch."

Tennison says that "for a while, we tried to work at home, but we realized that our residents needed us too much to be hiding from them." At first he asked for documentation from employers, as he normally would, but soon he dropped it. He waived the 9 percent late fee. He worked out payment plans rather than issuing notices to vacate. He set up a space for residents with a computer so people could file for unemployment and other assistance, and office staff helped track down tenants' checks.

Then he helped residents find new jobs. "We've recognized the situation for what it is, instead of instead of addressing it in the kind of old school way of 'you don't pay your rent, you gotta get out,' we're like, 'you can't pay your rent, let's look at why — and let's fix it.'"

He gathered leads from help wanted signs he spotted in the neighborhood and news in the paper about companies hiring locally, and he had his community manager text the information to tenants. Sometimes he and the manager tailored the leads, such as an auto-body repair shop or a place that needed house cleaning. "Just to help folks get back on their feet," he says.

Schools closing was another problem. Kids who had been getting free breakfast and lunch were suddenly at home, eating poorly or going hungry. Tennison saw a flyer from a local church offering to deliver food to children, and he signed up 20. "While the kids were there getting the lunch, the church realized pretty quickly that the adults were hungry too," he says. "They were tightening their belts and living on beans and whatever to make their car payment or to make their cellphone payment — without those two things, it's hard to find work and pay rent." The church increased their drop-off to 150 lunches, and leftovers were given to other hungry people in the neighborhood. The office was stocked with food so residents could discreetly take what they wanted, and Tennison, his wife and his manager volunteered handing out food boxes at the church.

He worried about making his own payments on a $4 million bank loan, and he felt badly that he wouldn't be able to make distributions to his investors, to whom he originally projected earnings of 9 percent annually. "I have about 18 people who trusted me with their life savings to invest in this apartment complex deal," he says. "And as much as I worry about my residents, I have to worry about them too. I don't want to lose these people's money." To stay afloat with a 36 percent increase in delinquency in 2020 while paying for constant maintenance expenses, mortgage, taxes and payroll, he received a loan from the federal government, which he hopes will be forgiven, and funds from the Small Business Administration.

Today Tennison says he is breaking even. "I'm on the knife edge of profitability and insolvency," he says. "This is not what I signed up for. It's a lot riskier than I thought it would be."

The situation for Tennison's renters has improved, somewhat. Relief money flowing in from the government helped, including direct payments, increased unemployment benefits and rental assistance.

More aid from the plan President Biden just signed will mean a great deal. "That will clean the slate for a lot of folks here and hopefully give them a little breathing room so that they can finally get their lives back on an even keel," Tennison says.

The job market has recovered more erratically. Many of Tennison's tenants have found work, though the going is tough. There are so many people looking that wages for the same jobs have declined. Some people had to take two part-time positions. Some have been finding odd jobs. And some who can't pay on the first are paying later in the month. Complicating matters, during school closures one parent has to stay home.

Tennison's currents residents — the ones who did not move out with an unpaid balance — still owe a combined $12,000 in back rent, he says. That's a vast improvement, which is the good news. But he worries.

"Our new, more compassionate business model has kept us afloat, but it is dependent on government support that is not guaranteed and does not come on a regular basis," Tennison says. "I would sleep better at night if my residents could pay their bills without needing government assistance."

The pandemic hurt high-end landlords too. Wayne Zussman owns three condominiums in Washington, D.C. "I've never had a day without rent in 35 years," he says, but urban living has fallen out of favor because of COVID. Compounding that, "People with no jobs or a cut in pay are not looking to move," he says. One of Zussman's condo has been vacant for three months and the others may soon be vacated too. He hasn't had a new tenant for the rental, but when someone finally moves in he's going to take extra precautions before renting to them during an eviction moratorium. "I'm a little leery of someone leasing the place and then saying, 'I can't pay you.'" Meanwhile, he's on the hook for expenses, including HOA fees and maintenance.

Dr. Djenita Jneid and her husband had been renting their former one-bedroom condominium home in a fashionable part of Houston, fully furnished, for $1,700 a month — below their cost. When COVID hit last March, the tenant stopped paying rent, Jneid says. The landlords gave her a letter to vacate and she said she would but never did. A judge agreed to eviction, but then the national moratorium was in place. Jneid says she told them the president said she didn't have to pay. She was not even interested in negotiating a payment plan, and she wouldn't respond to phone messages or emails. She now owes $17,000 in past due rent, and the landlords have been footing the bill for her housing for a year — paying HOA fees, which include some utilities and trash service, as well as the mortgage and property tax.

In addition, the couple, who are both doctors, could not use the condo for quarantining when they'd been exposed to COVID. Instead they had to pay for a hotel. At a recent court hearing, according to Jneid, the judge said the tenant had not made a good-faith effort to pay and ordered her eviction despite the moratorium. The landlords say they put copies of the eviction notice inside the door and on a side table. Jneid says the tenant finally moved out but took all of their furniture, their television and even a painting.

At this point, they are glad she's out and they don't plan to be landlords again. The experience soured them on the government's intervention. The moratorium "is so unjust and unidimensional," Jneid says. "It helps one section of society while hurting another. It encourages people to not pay rent and take advantage."

PC Wang is trying to be an understanding landlord, but this has upended his careful plans. He owns and manages three apartment buildings in Montrose, an area close to downtown Houston that used to be bustling with people at dozens of bars and restaurants. Vacancies were rare. Now, with restaurants, gyms and offices at a standstill, many of his tenants have fallen behind on rent. Vacancy is up to 20 percent. Of the eight units who are past due, one owes as much as $9,500 for the last 11 months, Wang says. "I know they are trying," he says. "I can understand. They just don't have the money." He tells tenants where to apply for rental assistance and some of the renters are using it. A few don't have internet and their phones have been disconnected, so Wang goes in person to tell them there is rental assistance available and he has them apply from his office.

In the meantime, Wang secured a government loan that doesn't require payments now — but the 3 percent interest continues to accrue. It frustrates him that the government didn't offer interest-free loans. Instead of making strides in paying off his mortgage, his debt is growing. "It is the landlords [who are] the group of people who get hurt most," he says. "I'm the one who gets stuck. Every month I owe more and more money. I'm going backward. I will never be able to pay it off. I can get by one day at a time, but I owe more money. I don't know what I'm going to do. I don't see my dream coming true."

Wang immigrated from Taiwan 50 years ago and worked in IT for years before taking his savings and investing in apartments. At 74, he's financially helping his two children and three grandchildren, with another on the way, and now he has less to give. He wishes he could hire a manager and retire, but right now he has negative cash flow. "You say this is a rich country — it's a joke," he says. "Everyone is struggling."

Yaeko Scott sure is.

‘Things Have Come Undone’

Scott, 48, was working as a full-time housekeeper at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome in New Orleans for a year when she was laid off with dozens of others last October. She was home with COVID — the second time she says she caught it on the job — when she got the news. She has been applying for jobs all over the city, but hiring is scarce and with only a high school education many jobs are not open to her.

Adding to the struggles, Scott's 30-year-old daughter, who shares her three-bedroom apartment, was laid off at her waitressing job due to the downturn and hasn't found a new job. Her 18-year-old son is actively applying but so far can't find work either. Her husband lost his job, too, and their marriage dissolved under the daily pressure.

Her rent is $1,215 per month.

"Things have come undone," she says. Her head is pounding from the constant worry. "You're wondering how you are going to eat. What do you do?" Owing $5,000-plus to her landlord, she says, "There is no way I can catch up with that." Late fees keep piling on. Once unemployment kicked in, she received $171 weekly and then $300 weekly in supplemental unemployment.

Even with the supplement, she says, it only covers utility bills, car payments and groceries. "It's hard to figure out how to get everything back on track," she says. "You can't touch the rent because you have to keep everything else on track. You want to pay it but you can't."

Scott had her car loan extended for two months to make up for two months of nonpayment, and she applied for rental assistance but she hasn't heard back yet. "You're fighting with everything that you have," she says, "but you're still failing."

With four in the apartment and no one working, times are tough. "They do all of that whining, sometimes you have to give them a picture of 'it could be worse,' " she says. She asked her daughter, son and 8-year-old granddaughter to gather things they no longer wanted. The pile included an old tent, two blankets, sweaters, a couple of jeans and tennis shoes her "ex" wasn't wearing. They brought it to some very grateful people living under a bridge.

It was a lesson for her family. "You have to learn how to deal with every issue, especially when it's something you cannot change," Scott says.

She is still unemployed and hasn't paid rent on her current apartment since September. She says the latest stimulus check will help her "knock out some things," but she hasn't received it yet. She's checking her bank account twice a day, but she knows it doesn't solve all her problems. "If I don't find a job, I'll be back in the same position," she says.

While her landlord has been understanding, Scott fears that once the moratorium is lifted, eviction notices will be served. "I don't know if they'll work with us," she says. "They are going to want their money. If we don't have the money, we're probably going to have to move. I don't know where. I would look for a two-bedroom house, not another apartment, because they're more willing to work with you."

She wants to make sure it's in a safe neighborhood, and she thinks she can find one for around $900 a month.

"They know everybody's in a situation right now," she says. "I'm just hoping they will understand why it got backed up. This is not a normal thing — for anybody."

Source: Read Full Article