‘Traumatic and Transformational’: Dad-of-Five Lived in Church for 41 Months Hoping for Aid in Immigration Case

Rene Alexander Maldonado Garcia — “Alex” to those close to him — did not know when he first found sanctuary in a St. Louis-area church in September 2017 that it would be his home for the next 41 months.

He wasn’t sure exactly what the next few weeks would bring, let alone the next few years.

On Feb. 24, for the first time since walking through the doors of Christ Church in Maplewood, Missouri, Garcia walked back out a free man.

For now, at least.

Garcia’s story can be told different ways by different people: To the immigration judge who first expelled him from the country in 2000, Garcia was an 18-year-old Honduran native who had entered the U.S. illegally. To the Immigrations and Customs Enforcement officials who detained him in 2015, more than a decade after he had returned to the country without detection, he was a target for removal — someone whom they had to be persuaded to release, under supervision. To the Trump administration, who had been brought to power after an anti-immigration campaign, he was a prime candidate for deportation.

Critics might point to a 2009 DUI conviction, for which he was fined and did not receive jail time.

But to Garcia’s community in Poplar Bluff, Missouri, he was known as a tireless worker and faithful husband and father — someone to personalize, and to complicate, one of the country’s thorniest issues.

“He’s just a good, honest guy that wants to work hard for his family. That’s a very rare thing these days,” one local developer said in 2017, as Garcia’s case was first gaining attention.

Back then, his family wasn’t sure what to do to bring him home — only what they could do to keep him from being sent away.

"It's terrifying," his wife, Carly, told the Riverfront Times in 2017. "It's terrifying to me that my family is not going to matter enough to take action."

Carly remembered then how, “in the beginning, I was against taking sanctuary. I was against him not doing what they were asking, specifically because I was worried about the repercussions for doing so.”

But then she woke one morning with a changed mind: “What am I doing? Why am I just giving up? Why am I just going to give him to them? What kind of wife would I be if I didn't fight for him?”

That fight — which continued to draw local media attention since 2017, as community members and religious leaders and some lawmakers rallied to Garcia — was won, if only temporarily, when Garcia, now 39, was at last allowed to leave the church.

Still, he remains under the threat of deportation to Honduras, away from his wife and five children, all of whom are U.S. citizens.

"The kids have grown up with this in their formative years," says Sara John, a religious advocate involved in Garcia's case. "His 6-year-old was 2½ when he moved into sanctuary. The children would ask the pastor, 'Why won't you let my dad come home?' "

How Garcia Came to Christ Church

Garcia first entered the U.S. — illegally crossing the border, which was the basis for his first expulsion — two decades ago, when he was 18. He was fleeing Honduras, which has been plagued by poverty and violence, and seeking a new home.

“He was removed right after his first attempt to come to the United States,” Garcia’s attorney, Nicole Cortes, tells PEOPLE. “In 2000, he entered without inspection, he was detained and an immigration judge ordered him removed and he was deported back to Honduras.”

A few years later, Garcia returned to the southern border but this time he entered without being detected by officials. He stayed off of the immigration radar until 2015, when he took his sister — who had just arrived seeking asylum — for an ICE check-in.

Cortes says Garcia was detained after ICE realized that he had previously been deported.

He wasn't removed, though. That's because, as Cortes explains, Barack Obama's administration twice granted him a year-long stay of removal — in Cortes' words, "a direct promise from [the government] that you present enough positive factors that it outweighs that you're in the priority category."

In other words, Garcia was allowed to stay in the U.S. so long as he periodically checked in with ICE officials.

The move was in keeping with Obama’s larger approach to immigration: Stymied by Congress, who could not reach an agreement on the reform he sought, Obama used the discretionary authority ICE has in its enforcement to avoid targeting certain groups of immigrants.

In a statement to PEOPLE for this story, ICE confirmed that Garcia was arrested in 2015 “and placed on an order of supervision, with a periodic check-in requirement.”

Then under President Donald Trump, ICE's priorities shifted. "Everybody was a priority" for deportation or detention, Cortes says, and Garcia's earlier agreement that he could stay in the U.S. "went out the window."

In 2017, Garcia's petition for a stay of removal was denied and his order of removal was reinstated. (ICE maintains it was because he “failed to comply with check-in requirements,” though his attorney says it was due to the change in enforcement that came with President Trump.)

Rather than risk his removal to Honduras — where he would be unable to seek re-entry to the U.S. for 10 years — Garcia found sanctuary at Christ Church in Maplewood for three and a half years.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free weekly newsletter to get the biggest news of the week delivered to your inbox every Friday.

There was no guarantee his plan was going to work that long, though.

The sanctuary provided by churches is a cultural rather than legal protection. It is, however, a concept that is centuries old and something of that is reflected in ICE's own rules. The agency discourages agents from conducting enforcement activity in sensitive locations like hospitals, schools, houses of worship, sites of public religious ceremonies and public demonstrations.

In recent years, a network of churches has emerged across the country, providing sanctuary to migrants from ICE.

Rev. Rebecca Turner, Christ Church’s pastor, spoke up for Garcia in 2017: “If we're going to take seriously following Jesus, then we have to engage with the world,” she told the Riverfront Times then.

Sara John, the executive director of the St. Louis Inter-Faith Committee on Latin America, tells PEOPLE that Garcia moving into Christ Church was “a tool for us to not only win some time and figure out longer-term strategies, but also to think about the community response and faith values that drive what justice looks like for the 11-13 million undocumented people here.”

‘Doing Anything He Could’

Until February, Garcia lived in an apartment in the church basement, spending most of his days “doing anything he could to distract him from feeling anxious and worried about being separated from his family,” John says.

That meant fixing cracks in the plaster walls, painting everything that needed a touch-up, re-wiring and helping with food prep in the kitchen.

Though he was safe from deportation, Garcia wasn’t able to see wife Carly, whom he wed in 2010, or his children as often as he would have liked.

For the first two years of his stay, Garcia’s family would make the three-hour drive from their home in Poplar Bluff to Maplewood. In 2019, they moved closer so they could visit him daily.

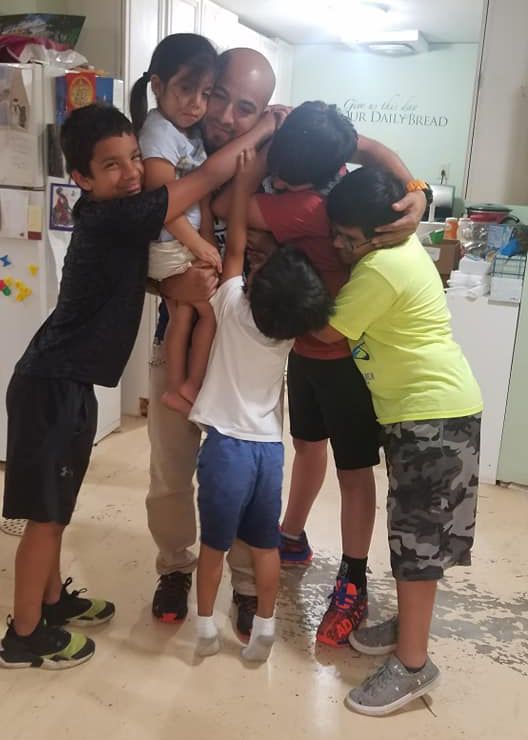

As rough as that time was on Garcia, his kids — 15-year-old Ayden, 14-year-old Caleb, 13-year-old Maddux, 8-year-old Xander and 6-year-old Arianna Lee — were not spared from the reality, either.

“It’s traumatic and transformational to grow up in this way and see your own government take actions that have such devastating consequences on your family,” John says.

Garcia’s teenaged sons joined his cause, writing letters to senators like Missouri’s Josh Hawley, asking for help and telling his story.

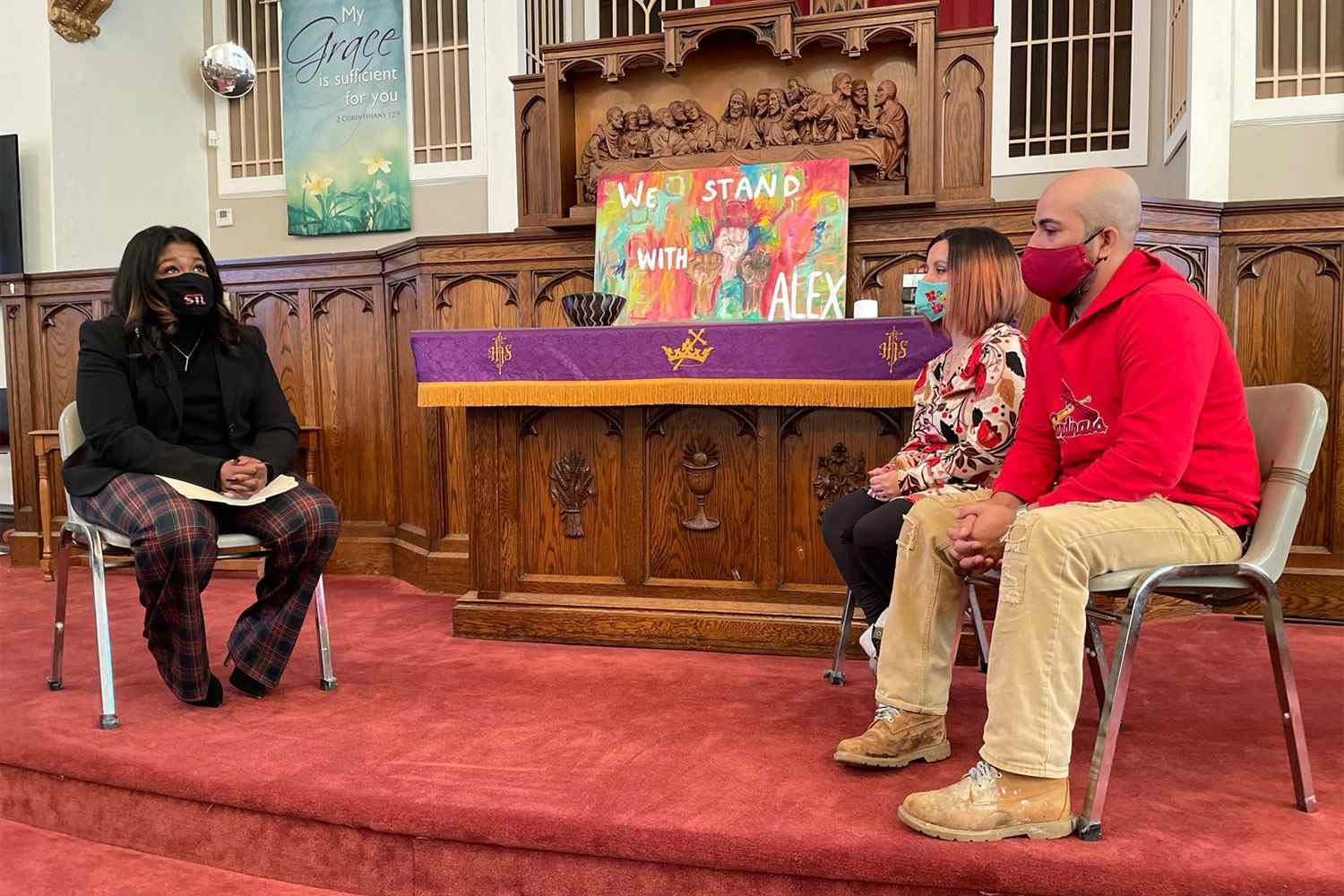

More recently, newly elected congresswoman Cori Bush, who represents St. Louis, has called for him to receive residency.

And there has been a change in the White House.

Garcia returned home in recent days only after his attorney grew confident that he would be safe outside the church walls.

Cortes tells PEOPLE that there still “isn’t any formal stay of removal or order of supervision or preemptive legal status,” but she says that ICE has made clear that they won’t be deporting Garcia any time soon, citing overstretched resources.

“They’ve very much said, ‘Alex Garcia is not a priority for removal. No resources will be used for his detention or removal,’ ” Cortes says.

For its part, ICE said that while it had discussed Garcia's case with his attorney “to explain the interim enforcement priorities,” it “does not confirm” whether or not it will order anyone’s removal or detention.

The agency said in its statement: “We continue to make determinations on a case by case basis in accordance with law and policy. The guidance provided for ICE focuses on the agency’s stated interim priorities, and does not prohibit the arrest, detention, or removal of any noncitizen.”

The Future for Now

Garcia is back home — taking his “ecstatic and on cloud nine” daughter, Arianna Lee, to school in the mornings and still lending a hand at the church as needed.

While his legal team is confident he won’t be removed by ICE any time soon, they continue fighting on his behalf “on any front,” Cortes says.

Because he re-entered the country after being deported, Garcia is subject to what is colloquially known as the “permanent bar” and can’t rely on his wife to obtain legal status. He would have to obtain permission to remain in the country another way.

In February, Rep. Bush introduced a private bill that, if passed, would make Garcia a permanent resident. In a virtual appearance at the time, he called Bush his family’s “champion,” but also urged attention be paid to other immigrants in the system. Carly, speaking alongside her husband, called the laws “outdated and unjust.”

“We’ve been living in this cycle of trauma for the last three-and-a-half years and it has felt unbearable,” Carly said.

Noting that the introduction (and the eventual passage) of such bills are “extremely rare,” Cortes tells PEOPLE she is also advocating with the legal arm of ICE to see about re-opening a stay of removal or determining some other way to alter Garcia’s immigration status.

His attorneys believe he is on "firm footing,” Cortes says, in that they don't believe he will be ordered removed any time soon.

(Of his past DUI conviction, she says, that it “doesn't define him, it was over a decade ago … [and] the positive things about him far outweigh one decision.”)

Still, Garcia still doesn’t feel entirely free.

Financially, he has been reliant on the church for his housing and meals. He’d like to be able to again take care of himself and his family — as he did before moving to Christ Church — but applying for a work permit or driver’s license would require an order of supervision.

According to his legal team, ICE has said it is stretched too thin to put resources toward such an order for Garcia.

“I think that Alex wants nothing more in the short term than to have work authorization so that he can support his family,” John tells PEOPLE. “Baseline, that’s what he wants the freedom to do: be a dad and be a husband.”

Source: Read Full Article