Pressure mounts on HSBC to axe ‘discriminatory’ staff pension cuts

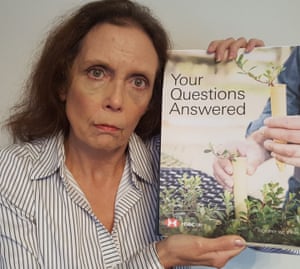

In three years, Sharon McGeough-Adams will start receiving her state pension, so she should be looking forward to taking it easy. Instead, she has become one of the central figures in a fight to ensure that pensions from HSBC are not reduced by up to £2,500 a year.

The 62-year-old campaigner started working for Midland Bank, which was subsequently taken over by HSBC, in 1976 and retired in 2013. When she reaches 66 in 2023, she expects that she will be hit with a close to £200 monthly reduction in her company pension because of a practice that enables the bank to reduce some former staff members’ payments.

The controversial practice has been greeted with fury from former and current staff, and has been labelled as being discriminatory against women, who are particularly badly affected. Now the bank is under sustained pressure to abolish the “clawback”, which allows employers to deduct the state pension from contributions made for its employees.

Clawback – known more formally as “pension integration” or “state pension deduction” – involves cutting a former employee’s company pension on the grounds that they also receive the state pension. It allows employers to deduct some, or all, of the basic state pension from company pension payments.

It was introduced in the 1940s and let workers pay lower contributions into their pension plans. The practice – which only applies to defined benefit occupational pension schemes – is legal, but mostly frowned upon. Often the first time people become aware of it is when they reach state pension age – which may be years after they start receiving their workplace pension – and discover that their company pension income has been reduced.

It is estimated that about 52,000 former HSBC employees are affected. The banking giant – which announced profits for 2019 of more than £10bn – has defended the policy, but campaigners have criticised it as “unjust and unfair”.

A number of MPs have supported the campaign via an all-party parliamentary group (APPG) on pension clawback, with Labour’s Clive Betts saying that he, and others, believe it is “discriminatory against women”.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission has also got involved, though earlier this year it ruled that the bank had not broken any laws.

Deductions vary widely: for example, for someone with 10 years’ service, who left in 1995, it is £376 a year, while for a worker with 34.5 years’ service, who left in 2015, it is £2,552.

At the centre of the opposition to HSBC is the 10,000-strong Midland Clawback Campaign action group. It succeeded in getting a resolution on the issue put to a shareholder vote, at HSBC’s annual general meeting in April this year. The resolution, calling for the removal of clawback, was not passed, but the group submitted several questions to the board, which answered some.

HSBC calls the practice “state deduction” and the way it works is complex. The formula is based on length of service (though it does not apply to benefits built up after June 2009) and the basic state pension when an individual leaves the bank’s service, though the latter was frozen at July 2015’s level. HSBC introduced the deductions in 1975, and the policy applies to scheme members who joined between then and June 1996.

Nicky, another woman affected by the problem, took early retirement on health grounds at 55 following 36 years at the bank. She opted to take a lump sum and a reduced bank pension of £7,397 a year, but says she was unaware that her pension would reduce by a further £2,194 once she was in receipt of her state pension.

During the 1990s, trade unions were claiming that clawback was being used quite widely by employers. In 1998 the Guardian reported on pensioners protesting about it outside Barclays Bank’s AGM. However, many major employers have either never made use of clawback, withdrawn it, or capped the amount they take.

For example, in 1999, the year after the AGM protests, Barclays capped the maximum deduction at around £950 a year. BP stopped making deductions the following year. The Post Office and Nestle were among other big names that took action at around that time.

The Midland Clawback Campaign group says that with clawback there is no link to salary or pension received, so it disproportionately penalises the less well-off.

It adds: “Employment policies of the 1970s and 1980s resulted in the majority of lower-paid staff being women.”

It also argues that the term “state deduction” is confusing, and that many scheme members had assumed it either referred to something the government did, or being contracted out of Serps, the old top-up state pension.

Betts says: “By and large, in this scheme, women have lower pensions – therefore, when the state pension is taken off their private pension, it’s a much bigger percentage on average that women lose than men. This can’t be right. They have been very unfairly treated.”

HSBC recently disclosed it had received an approach from the Equality and Human Rights Commission “on an informal basis”. This followed a complaint lodged by Betts and the group in late 2018.

However, in April, the commission said the legal advice it had received “confirms that HSBC’s position is not unlawfully discriminatory”. HSBC has told shareholders that scrapping the deductions would cost it about £450m.

The bank says its policy “might seem to impact lower-earning employees, many of whom are female,” but added: “The state deduction feature does not constitute indirect discrimination because it applies to and affects all members equally, irrespective of gender or other protected characteristics. The use of the state deduction is acknowledged expressly by the Equality Act.”

HSBC points out that the feature was “an accepted aspect of UK pensions practice that is recognised by legislation and continues to be maintained by a significant number of schemes today”. It adds that scrapping state deduction “would constitute a retrospective change” which would benefit some members and “be unfair” to others.

It says the pension scheme in question was one of the most generous within the group and remained competitive – it was a final salary, non-contributory scheme until mid-2009, when member contributions were introduced. It added: “Members of many other schemes, including our current UK workforce, will not receive a guaranteed income in retirement.”

The bank adds that the state deduction feature had been mentioned in member guides since 1975.

Source: Read Full Article