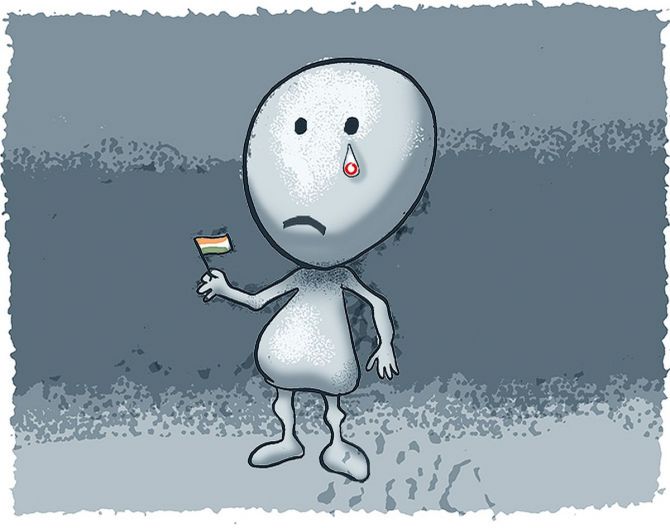

India’s telcos continue to dial the wrong number

India’s telecom sector has been through dizzying peaks, troughs, policy U-turns, court battles, brutal competition, and daily controversies.

India could go back to a private sector duopoly with just Reliance Jio and Bharti Airtel surviving the mayhem. The third player, Vodafone Idea, could be history.

1994:The government projects the market for mobile phones in New Delhi to be 30,000 subscribers.

When Essar builds a network of 100,000 subscribers, everyone is taken aback.

In Kolkata, Modi Telstra, which launched the first mobile network, was struggling to get 30 subscribers a day.

With a charge of Rs 18 a minute for voice calls and Rs 40,000 for a phone, this luxury was only for the well-heeled.

2020: The government projects the New Delhi subscribers number at 53 million, voice calls are free, and India is the largest user of data in the world.

A 4G phone costs Rs 500, the cheapest perhaps anyway in the world.

Mobile density soars from 4 per cent in 2001 to over 88 per cent today.

It is impossible to over-state the scale and impact of the telecom revolution.

At another level, it’s an industry whose overdependence on regulatory or policy interventions has not changed.

Nor has the impact of court orders on disputes.

In 1996, it was clear that the two licensees each who were operating in the 23 circles did not have a viable financial business model to survive.

The operators collectively spent a staggering Rs 27,000 crore as licence fee.

But at least eight of them were accumulating huge losses, with revenues not even matching their annual licence fee outgo.

The mobile dream was about to collapse.

But the government bailed out operators by migrating them from an annual licence fee to a revenue share model.

The duopoly of two players per circle was also changed with state-owned corporations allowed to join in.

This migration package happened just two years after the mobile revolution began.

All these years later, a court verdict – the Supreme Court’s judgement last year on telcos having to pay their AGR dues – could change the course of telecom once again.

India could go back to a private sector duopoly with just Reliance Jio and Bharti Airtel (at one time there were even 12 operators per circle) surviving the mayhem.

The third player, Vodafone Idea, could be history.

Stung by the payouts it has to make, financially stressed Vodafone Idea told the court that it lost Rs 6 trillion in revenues and as much as Rs 1 trillion of equity has been ‘washed away’.

Even if the court gave it 15 years to pay Rs 50,000 crore, it will have to double its ARPUs to stay afloat. That’s tough.

Looking back, the revenue share model was a game changer: the number of subscribers went up dramatically.

Twelve million were added between 1999 to 2002 compared with less than a million between 1995 and 1999.

The move was reinforced by the government and Trai through other key decisions.

For example, an interconnect regime was put in place to ensure level playing field between private and state-owned telcos, access deficit charges were reduced and later abolished, and forbearance on tariffs was introduced.

But the most impactful was the introduction of the calling party pay regime in 2004 which made incoming calls free.

Subscriber numbers boomed five-fold between 2004 and 2007, hitting 233 million.

Yet in the same period, the government created another crisis by allowing fixed-line operators to offer limited mobility within their circles in 2002.

GSM operators felt this was a backdoor entry to Reliance and Tata.

The then communications minister Arun Shourie pushed the two sides to arrive at an out-of-court settlement. Still, not everyone was happy.

Meanwhile, Reliance’s attempt to stir a data revolution in mobile was ahead of its time.

Monsoon Hungama offer – mobile phones bundled with data and talk-time for only Rs 501 – was snapped up.

The rates weren’t sustainable though.

Reliance was forced to write off Rs 4,500 crore as losses.

Not only Reliance, even the government made mobile affordable to the masses.

Then telecom minister Dayanidhi Maran pushed operators to cut roaming charges up to 56 per cent and introduce one-year validity cards.

Two more operators were allowed in every circle and the FDI cap was raised from 49 to 74 per cent.

Between 2004-05 and 2005-06, FDI inflow jumped from Rs 541 crore to Rs 2,751 crore.

Mobile companies were making money and the sector held promise.

But in 2008, controversial decisions by then telecom minister A Raja brought the industry to its knees.

First, he successfully conducted a 3G auction but limited the spectrum to five MHz an operator (against 20 MHz globally), leading to fierce competition.

Operators paid as much as Rs 67,000 crore for limited 3G spectrum.

Even the most aggressive of bidders, such as Bharti Airtel and Vodafone, did not have the cash to acquire pan-India 3G spectrum.

Telcos ran out of money, service roll outs were slow and 3G tariffs were kept high, restricting the expected data revolution.

Raja’s second decision was more catastrophic.

He changed the rules on licences to a first-come-first-served basis, allegedly to help his friends.

He offered four to five new players licences and suddenly there were a dozen odd players in each circle, prompting cut throat competition.

Tariffs dropped to 2005 levels.

The business looked unviable while customers had a field day.

The final nail in the coffin came when the Comptroller and Auditor General alleged that the government had made a notional loss of Rs 1.76 trillion by giving away spectrum at throw-away prices.

Raja was imprisoned and the case was subjected to a CBI probe which eventually found little to nail Raja.

Taking cognizance of the CAG, the Supreme Court cancelled 122 licences, including those of top global telcos.

These companies lost huge sums and global investors questioned India’s investment environment.

The storm, however, led to the first consolidation, with nearly five to six operators shutting shop.

Cut-throat competition was over, operators could increase realisation per minute, and subscribers were ready to pay for it.

The average revenue per user or ARPUs went up from under Rs 100 in Q4 FY13 to Rs 128 in Q1 FY16.

The industry Ebidta nearly doubled from Rs 29,500 crore in 2012-13 to an attractive Rs 54,000 crore in 2015-16, on a gross revenue of Rs 2.53 trillion.

But there were other worrisome winds of change.

It was clear that all spectrum would be auctioned by the government and with the introduction of the UASL licence, spectrum would be de-linked from services so that telcos could use any spectrum for any service.

The auctions that followed in 2015 saw a massacre, especially in the 900 MHz band (the licence for this band was expiring for incumbents but it was a popular band for 4G), and prices went up by three to five times.

The telcos spent more on spectrum (Rs 1.75 trillion in just two years, 2015 and 2016) than they had spent since launching their services (Rs 1.5 trillion).

That was not the only challenge.

Mukesh Ambani unleashed a disruptive strategy offering a 4G network across the country while his competitors were far behind.

Ambani made voice free, offered data at rock bottom prices, and made the services free for six months, despite complaints by rivals.

Companies like Vodafone Idea who were sceptical about the future of 4G, had to change tack.

Financial mayhem ensued.

Incumbent operators not only had to pay for the huge loans they had taken to finance spectrum costs, they had to invest more to catch up with Jio – and compromise on margins by dropping their tariffs to avoid losing too many customers.

The industry debt burden skyrocketed from Rs 2.8 trillion in 2015 to Rs 7.7 trillion in 2018.

ARPUs, which had hit an attractive Rs 141 in Q1 FY17, sank to half.

Industry Ebidta also fell by half from Rs 54,000 crore in FY 16 to a mere Rs 24,400 crore in FY 19.

The Jio onslaught forced the second consolidation.

Many operators like Rcom and Aircel went to NCLT.

Tata and Telenor sold their assets at throwaway prices.

The market pecking order changed. Jio was the number one player in revenue share, ousting Bharti and Vodafone.

But Jio’s relentless push to grab 500 million mobile customers eased and it moved away from a pricing war last December.

Tariffs as well as ARPUs slowly moved up.

The lockdown has also helped in increasing usage and therefore revenues for all operators.

Beyond 2020:The future of telecom will depend on two things: how much time the Supreme Court gives them to pay the AGR dues and whether Vodafone Idea is game.

Source: Read Full Article