Why Amit Mitra is important to Mamata

No longer Bengal’s finance minister, Amit Mitra, Mamata’s principal chief advisor, will still advise and aid the ‘chief minister and finance department on all matters relating to management of state finance’, represent the ‘state government in national and international events/meetings/committees’ and examine ‘important proposals/files and policy issues relating to financial matters referred to him for advice/views’.

Ishita Ayan Dutt reports.

West Bengal, 2011: The Mamata Banerjee-led Trinamool Congress was looking to bring the Left Front’s 34-year rule to a halt.

Amid a raging battle across the state, one assembly constituency — Khardah in North 24 Parganas — was drawing attention.

Khardah was the turf of Asim Dasgupta, Bengal’s longest-serving finance minister, a doctoral student of economics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

His opponent — Amit Mitra — a PhD in economics from Duke University and secretary general of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) — was preparing to give up the high-brow world of sharp suits and thin ties for the heat and dust of politics.

The rest is history.

Banerjee’s party decimated the Left and Mitra became one of the many giant slayers in the historic elections that saw the defeat of 26 ministers.

When the government was formed, Mitra was appointed state finance minister.

In two years, he was handed the additional responsibility of industry and then information technology, portfolios that he held till the assembly elections earlier this year.

Mitra did not contest the 2021 assembly election on health grounds but continued as finance minister when the government was formed.

To continue in office, he had to be re-elected as an MLA in six months. That window closed last week.

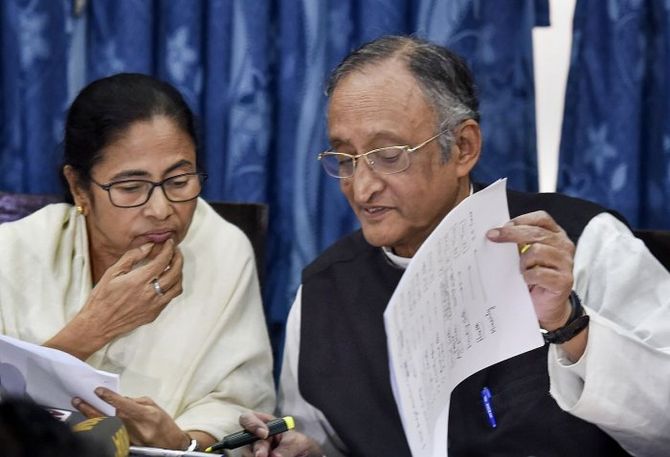

But Banerjee has retained him as her principal chief advisor and of the finance department (Banerjee has kept the finance portfolio and Chandrima Bhattacharya has been appointed minister of state).

Mitra will have the rank of a cabinet minister and from the finance department’s notification, he appears to have sweeping responsibilities, raising eyebrows in administrative circles.

These range from ‘advising and aiding the chief minister and finance department on all matters relating to management of state finance’ to ‘representing the state government in national and international events/meetings/committees and examining important proposals/files and policy issues relating to financial matters referred to him for advice/views’.

It’s not hard to fathom why Mitra is important to Banerjee.

In the last 10 years, he has walked a tightrope between managing the state’s debt problem and mobilising resources for Banerjee’s numerous social schemes — Kanyashree (financial assistance to girls for pursuing higher education), Krishak Bandhu (for farmers and sharecroppers), Swasthya Sathi (universal health scheme), Lakshmir Bhandar (basic income support for women) are the show-stopping ones.

“The policies of this government are geared towards the under-privileged. Dr Mitra had to walk through stringent financial constraints to implement them,” Abhirup Sarkar, former professor of economics at the Indian Statistical Institute, pointed out.

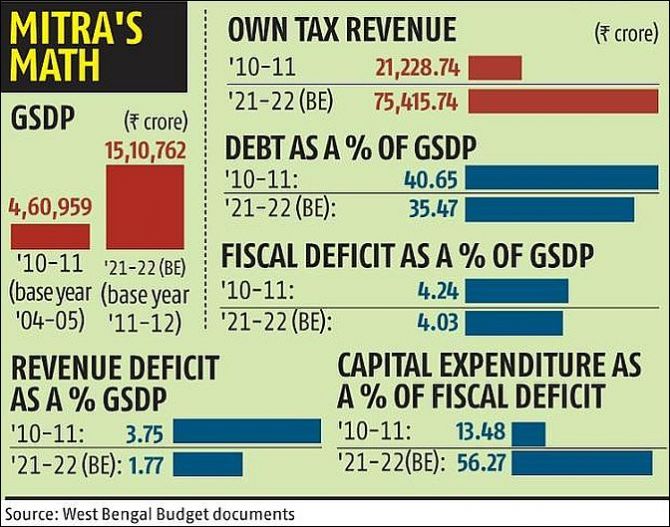

The focus of the government is underscored by social sector expenditure, which is projected to rise more than nine times between 2010-11 and 2021-22 to Rs 62,671 crore.

Mitra explains why. “During COVID-19 and earlier, we have been following a demand stimulation model. That means putting money in the hands of the people, which results in demand creation.”

“That’s why West Bengal showed a 1.2 per cent GSDP (gross state domestic product) growth in the middle of Covid, whereas India’s GDP dipped to negative 7.7 per cent in 2020-2021,” he said.

The government also spent on asset-creating infrastructure such as roads, schools, colleges, hospitals and water works.

But debt has jumped, though it is widely known that Mitra inherited quite a burden.

Debt, in 2010-2011, had stood at Rs 187,387 crore and is estimated to increase to Rs 535,833 crore in 2021-2022.

However, as he pointed out, “The debt to GSDP ratio has come down, which is the biggest achievement. If the ratio had gone up, I would have had to pull back.”

The revenue deficit-GSDP ratio seen over 2010-2011 also looks favourable (see table).

But ICRA Chief Economist Aditi Nayar noted that the state’s revenue deficit increased to 1.6 per cent of GSDP in FY2020 from 1.1 per cent of GSDP in FY2016, led chiefly by a decline in central transfers.

But leverage levels improved between FY2016 and FY2020 partly led by a decline in the state’s stock of guarantees, she pointed out.

The fiscal deficit to GSDP ratio targeted at 4.03 per cent, according to 2021-22 (BE), was also lower than 2010-2011.

One of the ways Mitra managed to balance expenditure is by growing state tax collection.

From the level in 2010-2011, it is projected to increase by 3.57 times to Rs 75,416 crore in 2021-2022, largely on the back of initiatives centred on e-governance that plugged leakages.

But as an economist pointed out, “What West Bengal needs is big industries and big-ticket investment. The state’s growth in industry largely rests on MSMEs that need subsidies and are not efficient; MSMEs cannot drive growth.”

At 8.9 million, West Bengal accounts for some 14 per cent of the total MSME units — among the largest after Uttar Pradesh.

Credit flow to the sector has increased over the years and stood at Rs 87,000 crore in the last fiscal.

Mitra explained, “Due to our demand stimulation model, the supply chain in West Bengal was not broken as much as elsewhere in the country during the pandemic and so there was appetite.”

But the importance of big industry is not lost on Mitra.

To woo them, he started glitzy investor meets such as the Bengal Global Business Summit, often considered important marketing tools in competitive federalism.

The summits have seen participation from some of the biggest names from India Inc – from Mukesh Ambani to Lakshmi Mittal and Sajjan Jindal.

According to Mitra, the five editions from 2015 to 2019 generated proposals worth Rs 12.32 trillion.

But questions are being raised about these numbers.

Governor Jagdeep Dhankhar sought details of the investment proposals and the exact status last year and recently.

According to Mitra, 50.27 per cent of the investment proposals between Bengal Global Business Summit 2015 and Bengal Global Business Summit 2018 went into implementation mode.

For Bengal Global Business Summit 2019, Rs 71,464 crore was under implementation (the figures were part of the letter to Dhankhar on September 24, 2020).

The IT sector promises some action with a bunch of companies taking up space at the proposed 200 acre IT hub called the Bengal Silicon Valley.

TCS has taken up 20 acres to build a second campus, Reliance Jio has taken 40 acres for a high-tech data centre, and so has Airtel.

The much talked about Infosys development centre and Wipro’s second campus are works in progress.

Plus, a sizeable IT sector already exists.

“TCS employs around 44,000 people, Cognizant 20,000, Wipro 10,000-12,000. HSBC has a significant part of their back office here,” Mitra pointed out.

The government is also stepping on the gas on two projects that may be game changing: A proposed greenfield port at Tajpur in East Medinipur and the development of Deocha Pachami coal block in Birbhum, considered to be the largest in India.

As principal chief advisor to the chief minister and the finance department, will Mitra be able to conjure up resources for the projects like he did for the welfare schemes?

Will he play an active role in bringing India Inc’s who’s who to the Bengal Global Business Summit slated for April next year?

Will he continue to lead the battle against the Centre on GST?

With his enlarged powers, many will be waiting for these answers.

Source: Read Full Article