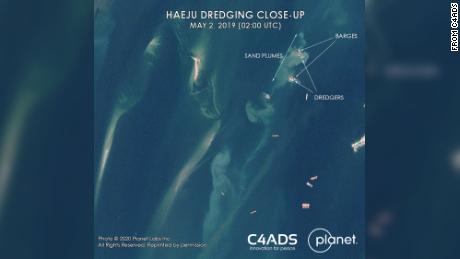

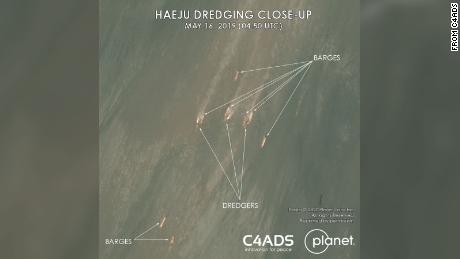

This handout image courtesy of C4ADS shows ships in the waters off the coast of the North Korean city of Haeju.

Hong Kong (CNN Business)It was May of last year when Lucas Kuo and Lauren Sung noticed something strange: more than 100 ships gathering in the waters near Haeju, North Korea.

As part of their work at the Washington-based Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), a nonprofit that analyzes and investigates security issues using big data, the two analysts keep an eye on traffic in North Korean waters and further afield in Northeast Asia.

They do this because Pyongyang has been accused of selling coal and other valuable goods, sometimes in very big quantities, on the high seas to get around the prying eyes of customs officers, who must enforce United Nations sanctions on North Korea. Instead of moving goods into a port before trading, North Koreans supposedly just move them from one ship to another at sea and lie about their origins.

These “ship-to-ship transfers” can rake in tens of millions of dollars for Kim Jong Un’s cash-strapped regime, depending on what’s sold.

They are meant to be fast and discreet, and usually involve a few ships at most. But Sung and Kuo kept seeing dozens of ships mysteriously sailing to North Korea.

Something was up.

What Kuo and Sung went on to discover was a massive operation allegedly worth millions of dollars involving 279 ships which appeared to be skirting international sanctions on North Korea.

But these ships weren’t being used for running guns, dealing drugs, offloading counterfeit cash or trafficking endangered species, crimes North Korea is notorious for worldwide. They weren’t even carrying coal, Pyongyang’s most profitable export.

They were being used to dredge and transport sand. That may seem innocuous, but North Korea is barred from exporting earth and stone under United Nations sanctions passed in December 2017. Trading North Korean sand is a violation of international law.

Despite those measures, North Korea raked in at least $22 million last year using “a substantial sand-export operation,” UN investigators said in a report released in April. One unnamed country supplied the Panel of Experts on North Korea, as the investigators are formally known, with intelligence claiming that Pyongyang sent one million tons of sand abroad from May 2019 until the end of the year.

The scheme was prominently featured in the panel’s annual report. Alastair Morgan, who coordinates the UN panel that monitors sanctions on North Korea, said in an email that the report’s authors decided “the large scale and the significance” of the operation warranted top billing.

The UN report didn’t cite C4ADS’ data. Morgan said his team submitted their draft in February, before Kuo and Sung published their research in March.

Piecing together the clues

Kuo and Sung watched the ships for several weeks before noticing a pattern. All of those showing up in North Korean waters had a link to China. Some were flying Chinese flags. Others had Chinese names.

Ship-to-ship transfers usually involve vessels registered to small countries where regulation is cheap and oversight is lax — boats flying a so-called flag of convenience.

But maybe these weren’t ship-to-ship transfers, the pair thought. They realized they needed more information before they could come to any conclusions.

So they turned to satellite imagery, perhaps the most important tool among the growing open-source intelligence community. The photographs they got their hands on showed clouds of sand under what appear to be dozens of barges and dredgers, evidence that earth was being pulled up from the bottom of the sea en masse in North Korean waters.

Sung did some research into North Korea’s history of sand sales and dredging, and everything quickly clicked.

“We found plenty of reports from the early 90s to the present indicating that rather than this kind of being anything new, North Korea has always been exporting sand to a lot of its neighboring countries,” Sung said.

Sung said it now appeared “there was a conscious effort to do this under the radar.”

The importance of sand

Modern civilization is built on different types of sand. It’s a key ingredient in concrete, glass and even the processors that power the electronic device you’re reading this on. Humanity consumes about 50 billion tonnes of sand per year — more than any other natural resource on the planet except for water.

Its supply may seem limitless, but there’s only so much of it to be dug up and removing it from the earth can have environmental consequences.

The sand that blankets the world’s deserts is too fine to use in construction because it doesn’t bind well. River sand is typically the best for making cement. Sand from the bottom of the ocean works too, but it needs to be washed and desalinated before it can be used.

Pyongyang has seemingly cashed in on the sand trade for years. Years ago, when North and South Korea did significant business together, sand was Pyongyang’s most valuable export to its southern neighbor, according to media reports at the time. North Korea sold $73.35 million worth of sand to the Republic of Korea in 2008, though South Korea stopped buying North Korean sand shortly after.

But there’s an even more important customer bordering North Korea: China, the world’s most voracious consumer of sand.

During the 2010s, the country underwent a construction boom unprecedented in world history — Beijing used more concrete in 2011 through 2013 than the United States did in the entire 20th century. Though the building boom has slowed today compared to its peak, China still uses more concrete than the rest of the world combined.

What was going on?

Neither Sung or Kuo knows what happened to the million tons of sand after it was shipped to various Chinese ports across the country’s coast. Sand smuggling is a major issue in China and the trade is notoriously opaque.

China’s Ministry of Public Security, which did not respond to CNN’s request for comment for this story, launched a campaign at the start of last year to crack down on illegal sand operations along the Yangtze River. By October, authorities had investigated 90 groups in 10 different provinces and seized $251 million, 305 sand mining vessels and 2.88 million cubic meters of sand, Chinese state media reported.

JUST WATCHED

How close are China and North Korea?

MUST WATCH

Beijing so far has denied allegations of any wrongdoing when it comes to the North Korean operation. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a statement to CNN that the country “has always fulfilled its international obligations” and abides by UN sanctions.

In the UN report, China responded to the allegations by saying the country “attached great importance to the clues provided by the panel in relation to the smuggling of sand” but that authorities in the country were “unable to confirm that the sand had been transported to Chinese ports.”

North Korea has not publicly responded to these specific allegations, but often refers to the sanctions as “hostile acts” and questions their legitimacy.

It’s also still unclear who was digging up the sand and why they were doing it.

The who question is the more difficult one to determine. None of the 279 of the ships involved in the scheme that C4ADS identified had an IMO number — a unique identifier that’s tied to a tracking device on board. Ships caught without them or obscuring them are often stripped of their registration in their home countries, which makes it almost impossible to enter a port. But without IMO numbers, it’s hard to tie these vessels to particular companies or people.

The why question has a few possible answers.

It’s possible North Korea sold the dredging rights to a Chinese company, Sung and Kuo said. Sand isn’t particularly difficult to mine, but it’s a logistical nightmare. The cost of washing ocean sand, storing it and transporting such a heavy product quickly adds up.

“Unless you’re really working at scale, it’s not something that’s particularly profitable,” Sung said.

But there’s another possibility: that Pyongyang was less interested in the sand itself and instead wanted to deepen or expand Haeju port. North Korea could have contracted a company with a fleet of ships based in China to do the dredging and let them keep the sand as payment.

Whatever the purpose, it’s up to individual countries to uphold UN sanctions — the international body doesn’t have an enforcement arm.

Kuo said he’s still surprised the operation stayed under wraps for so long, despite the fact that so many ships — and possibly people — were involved.

“This is one of the most unique cases of North Korean sanctions evasion behavior that we’ve seen,” Kuo said.

“We are still perplexed.”

Source: Read Full Article